All About Vermouth: Categories, Regulations, and Products

Γιαννης Κοροβεσης•Articles

This post is also available in: Greek

I will state it outright and without hesitation: I consider vermouth to be one of the most versatile alcoholic beverages. It is excellent on its own, neat or over ice, as well as in cocktails, mixed with a soft drink, at almost any temperature you prefer, across seasons, at noon, in the afternoon, or at night. While many people have only discovered it in recent years, thanks to the rise of Negronis and similar concoctions, vermouth has enjoyed great popularity in Greece long before cocktail bars even existed. Perhaps this is why its resurgence has been so seamless. In this article, you will find all the (useful) information I have gathered over the years—knowledge that I believe will be valuable to both bartending professionals and spirit enthusiasts. Some of this information may be familiar, while other details might be entirely new, but in any case, this is a text you can always refer back to when seeking any vermouth-related information.

What is Vermouth?

Vermouth is an aromatized and fortified wine—a wine-based alcoholic beverage (usually white wine) infused with herbs and spices, then fortified with a distilled spirit to increase its alcohol content, and finally, a varying amount of sugar is added.

Vermouth is the most distinctive subcategory of aromatized and fortified wines and takes its name from its primary botanical component: wormwood. The German word for wormwood is wermut, which inspired the drink’s name. Using the Latin term Artemisia absinthium for branding would have been impractical, though it might have been more stylish to adopt the Greek equivalent, Artemisia.

By nature, due to the maceration of wormwood and other bitter botanicals, vermouth has an inherent bitterness. However, with the extraction of additional ingredients and the addition of sugar, it can develop herbal, fruity, spicy, and varying degrees of sweetness.

The History of Vermouth

Traditionally, vermouth, as we know it from bars today, was first produced in the Savoy region, an area that no longer exists as an independent entity. The House of Savoy, one of the most renowned royal families in history, hailed from this region. Originally from Switzerland, the family is said to have Celtic and Roman roots, and their administrative influence once extended as far as Sicily. They played a pivotal role in the unification of Italy and, of course, gave humanity the wonderful creation of vermouth—both dry and sweet—using herbs that grew abundantly in the Alpine region where the Duchy of Savoy was established.

Following the Italian Unification in 1860, Savoy was divided between two countries: its northern part, including Chambéry, Nice, and Annecy, was annexed by France, while its southern part, with Turin as its main city and former capital, became part of the newly unified Italy.

Given the rich herbal landscape of the region, locals had been experimenting with infusing wine with botanicals for centuries, producing numerous recipes with varying herbs and sweetness levels. Over time, Chambéry became known for producing dry vermouth, while Turin specialized in sweet ones. This is why, historically, you will find references in cocktail books to French dry vermouth and Italian sweet vermouth.

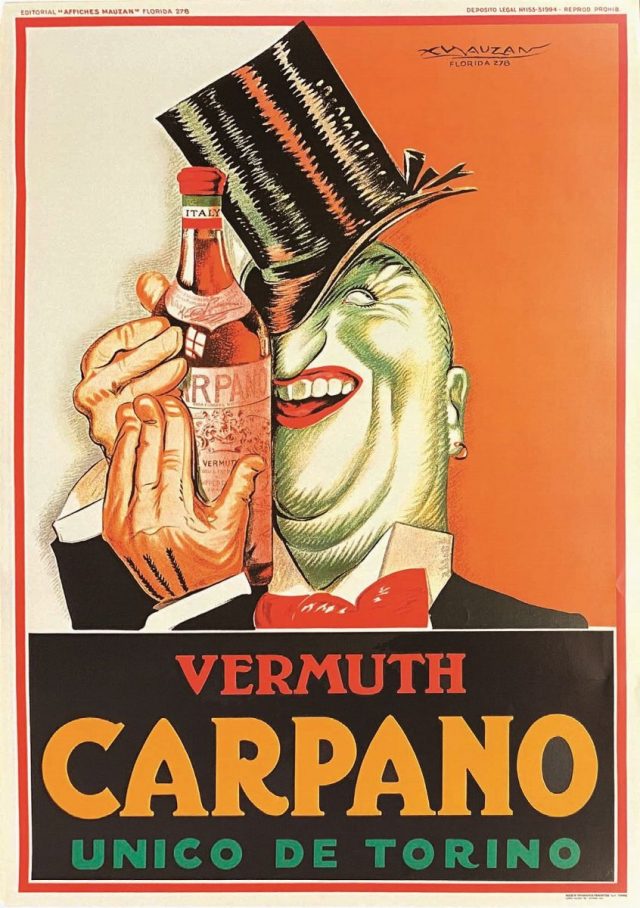

The first recorded production of sweet vermouth in Turin was by Antonio Benedetto Carpano in 1786, while Joseph Noilly was the pioneer behind dry ones in France, creating the iconic Noilly Prat recipe in Lyon in 1813.

Regulatory Framework

Today, European Union regulations for aromatized wines require that they contain at least 75% wine base and have an alcohol content between 14.5% and 22%. According to EU Regulation (EU) No 251/2014, vermouth must contain some form of wormwood—most commonly Artemisia absinthium, though Artemisia pontica and Artemisia maritime, among others, are also permitted.

Vermouth may be fortified with any distilled spirit, from neutral high-proof alcohol of agricultural origin to wine distillates such as brandy. For sweetness, a variety of sweetening agents can be used, including sugar in various forms, caramel, honey, or grape must.

The EU categorizes vermouth by sweetness levels:

- Extra Dry: <30 g/L sugar

- Dry: <50 g/L sugar

- Semi-Dry: 50–90 g/L sugar

- Semi-Sweet: 90–130 g/L sugar

- Sweet: >130 g/L sugar

As for geographical indications, within the EU, only one Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) exists for vermouth: Vermouth di Torino. This category comes with stricter production guidelines, requiring at least 0.5 g/L of wormwood. There is also a higher-quality designation, Vermouth di Torino Superiore, which must have a minimum alcohol content of 17% and use at least 50% wine sourced from Piedmont.

French dry vermouths, once recognized as PGI Vermouth de Chambéry, lost their protected status in 2000 and are no longer legally recognized under EU law.

To complicate matters further, under EU regulations, vermouth falls under the broader category of aromatized wines, alongside bitter aromatized wines, which include:

- Quinquina wines: Wine-based beverages infused with quinine extract (e.g., Byrrh, Dubonnet).

- Bitter vino: Wine-based beverages infused with gentian root (not to be confused with gentian liqueurs like Suze).

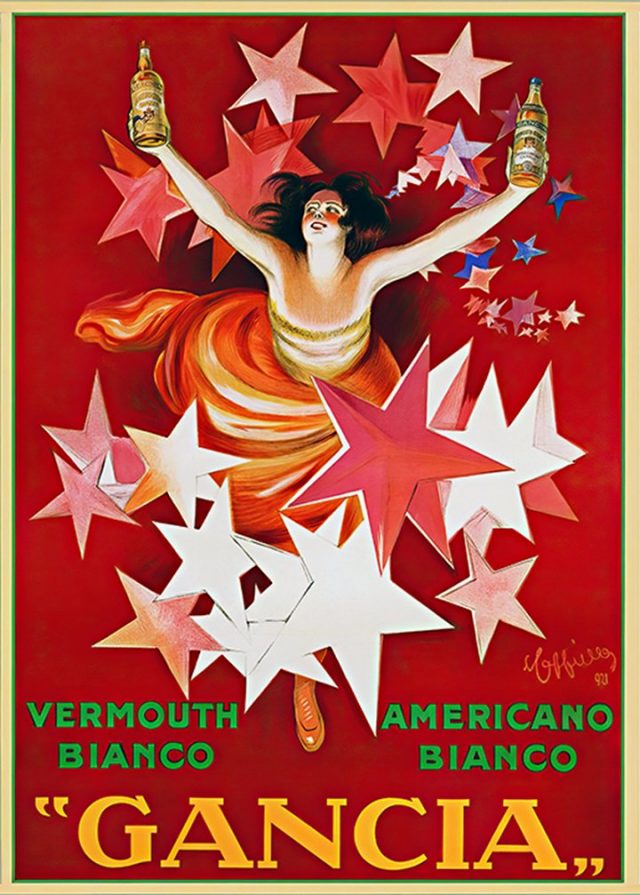

- Americano: A combination of gentian and quinine, historically an Italian response to French quinquina wines. Notable examples include Cocchi Americano and Savoia Americano Rosso.

Vermouth Around the World

Vermouth can be produced anywhere in the world, and indeed, it is—with notable examples beyond France and Italy including Vermouth de Reus in Spain (not PGI-certified) and various American vermouths, where regulations are less stringent and do not always require wormwood.

White, Red, Yellow, and… Blue?

While EU regulations categorize vermouth by sweetness, they do not classify it by color—except in broad terms: white vermouth ranges from pale yellow to amber, while red vermouth covers all reddish hues.

Traditionally, red are always sweet or semi-sweet, while white can be dry or sweet. However, there are also rosé and rosato , which tend to be fruitier and more delicate, with fewer spice-forward aromas.

French vermouths are mostly dry (labeled sec or dry), but there are also sweeter French versions labeled blanc or ambré. Similarly, while Italy is famous for red vermouth, it also produces white sweet vermouths labeled bianco or ambrato. If you want to make a Martini with white Italian vermouth, be sure to choose one labeled dry, extra dry, or secco, rather than bianco.

Like all wine-based products, vermouth oxidizes once opened and should be stored properly to maintain its quality.

Experiment with different vermouths, discover new recipes, and explore various techniques and styles. Turin vermouths remain the gold standard, offering remarkable craftsmanship and tradition. French vermouths, on the other hand, exhibit an unmatched elegance, with floral and refined characteristics. As for American, innovation and bold experimentation reign supreme—expect unique flavors and high-quality products that will surprise and delight you.